This entry is for chemical darkroom printers, but those who print strictly digital might find it of interest as well, as it covers some of the same techniques, and even terminology, used for inkjet work. It takes up the discussion after the test print stage where overall exposure time has been determined.

This entry is for chemical darkroom printers, but those who print strictly digital might find it of interest as well, as it covers some of the same techniques, and even terminology, used for inkjet work. It takes up the discussion after the test print stage where overall exposure time has been determined. After you have determined the proper overall exposure time for the negative, you may discover that certain tonal areas are not reproducing to your satisfaction on the print. For example, some highlights may be too harsh and lack detail, or some shadow areas are blocked up and lack separation. Before you go on to any mechanical steps to correct this problem, recheck your testing procedures. First off, take another look at your negative. Are there tones available that you just don't see in the print? Have you squelched your values to the point where the sacrifice is too great? Is your paper contrast grade too high or low? If it's too high, you may be causing a blockage in highlights and/or shadows. If it's too low, your highlights may be fine but your blacks are weak or, conversely, your blacks are fine but your highlights lack sparkle. Is overall exposure time correct?

Recheck your test strips and ascertain whether another time may yield a better tonal scale. If all these backup checks don't reveal the source of the problem you may simply have a situation where the negative itself doesn't have the information you need, or the contrast of the negative is such that a normal printing paper simply can't handle the range of tones. This is when dodging or burning in may come to the rescue.

DODGINGWhen you hold back the light from a select portion of the negative as it's being projected onto the paper you are dodging. Generally you'll need to dodge during printing when you fail to compensate properly for scene contrast in film exposure. A typical situation that forces dodging is when your principal subject is highly backlit, or when a portion of a subject is obscured in a bothersome shadow, such as under the brim of a hat. In each case, the area to be dodged has not received enough exposure, and is quite underexposed in relation to the rest of the image. You also may have to dodge a portion of a landscape scene when, for example, the sky is quite bright and the land becomes underexposed because you failed to compensate, through exposure or filtration, to bring the brightness values into a printable balance on the film. Whatever the reason, dodging is always used to help bring detail into underexposed shadow areas, as it keeps the darker tonal areas from being overexposed, or printed too dark on the print. This is accomplished by holding back some of the printing light during the overall exposure.

Dodging should never be overdone, as too much will destroy the tonal integrity, or flow, of the overall image. Shadow areas are truly darker than the rest of the image, but they shouldn't be weaker in tonal rendition. An over-dodged area will stick out like a sore thumb, and will look "muddy" and weak. Better to dodge with a light touch; better yet to work it out in negative exposure.

The best dodging tool is a small piece of cardboard taped to the end of a flexible, but sturdy wire; a thin coat hangar wire works admirably. Before you do your final print, practice a bit with the focusing light on. Place the end of the dodging tool between the light source and projected image and cover the area to be dodged. Now feather, or move the blocker back and forth quickly over the area. Don't just place the blocker over the area and hold it there-you'll create a tonal edge that's simply too forced and obvious. Work it like a swivel stick and keep stirring.

There's no hard and fast rule about dodging, but it's usually best to limit dodging to less than one-quarter of the total exposure time; any more and the effect may be too obvious. Thus, if total exposure time is twenty seconds, dodge for no more than 5 seconds. If you still can't get detail in the area you may be working with a lost cause and/or may be working on the wrong contrast paper for that particular negative. Experiment with a number of prints to get the right proportion of dodging to overall printing times. If you blend your light well you may be able to get away with a higher proportion of printing to dodging time.

BURNING-INWhen you add exposure to select portions of the print over and above the tested printing time you are burning-in. Generally, you burn in to add detail or texture to highlight areas, although you may also burn in dark areas to get blacker-blacks or to obscure shadows areas for a more dramatic presentation. There's also a technique known as edge-burning, which adds a subtle touch of exposure to the sides of a print.

First off, follow the same double-checks discussed in dodging to make sure that the cause of your problem isn't improper paper contrast selection or too little printing time. If the contrast is too high you may have good separation in your shadow areas but harsh highlights; if the printing time is too little your blacks will be weak and there will be no details even in mid-highlight areas.

In general, you'll be burning in to counter the harshness of contrasty scenes, where the brightest tonal areas (those areas on the negative with the greatest density) print with little or no detail. Subjects may include artificial light sources in low light scenes, reflections from metallic objects, and any area that receives too much exposure on the negative vis a vis the rest of the image, thus causes an imbalance of densities.

When you add exposure time over and above the normal exposure you are adding print density to select areas. This is accomplished by allowing light to hit certain areas of the print while holding it back from the rest of the projection. You can do this with your hands, with holes cut out in opaque cardboard, with the edge of a board, or by using templates, or forms cut out to match the areas that are to be blocked. Let's look at these one at a time.

If you've ever used your hands to make shadow plays on a wall you have an idea of what a versatile tool your hands can be for burning-in. Nearly any shape can be created by manipulating your fingers and palm, from straight lines to curving arcs. In addition, you can use both hands to create a funnel of light and can vary the amount of light going through by simulating the aperture on a lens by moving your hands in and out. Hand burning-in takes some practice, but as you gain experience you'll find it's very flexible.

The most common way printmakers burn in is with a hole cut in a piece of opaque paper or cardboard. Once the area to be burned in is identified, you cut a hole out in the paper or card that corresponds to the area (the larger the area, the greater the diameter of the hole), place the paper between the light source and the paper and feather the light onto the area. As you'll see, the farther away you hold the card from the paper surface the greater the area of the projected circle of light; it works just like a cone. Two tips: 1)Make sure that the burning in tool is quite a bit larger than the printing paper on which you're working; this ensures that you'll have no unwanted light leaking over the edges of the burn card onto the edges of the printing paper. 2) Burn by blending the light onto the area rather than just holding the burn card in one spot. As with dodging, creating a "no seam" look, where tones flow from one area of density to another, is critical.

One advantage of working with an opaque card is that you don't have to watch the light hitting the paper on the easel itself. By holding the burning tool above the easel you can see exactly where the light is playing on the surface by looking at the card itself. Naturally, having a white card helps. This close-hand viewing is an invaluable technique, as it makes what can be a clumsy experience into a smooth operation.

You can also use a card to burn in edges, corners, or a large horizontal or vertical area of the print (such as horizon lines). In this case you use the same blending, or feathering technique to get a flow of tones. Again, watch the areas not getting additional exposure on the surface of the card.

The last technique for mechanical burning-in is used when a highly amorphous shape, or unique form, must get additional exposure. (This can also be used for dodging.) Here you'll be cutting an opaque template of the area by laying a cardboard or thick paper on the projected print and sketching out the form. You then cut out the form and place it over the printing paper during exposure. If you use this technique, keep in mind that you may have to do additional blending with the small cutout burn card to keep the tonal borders from looking false. This is a tricky technique that requires practice to get right.

You can also burn and dodge and get varying grades of contrast on the same print by using a split-filter printing technique with variable-contrast papers. This opens up even more possibilities for solving underexposure (dodging) or overexposure (burning-in) problems, and is a way of solving some problems that can't be handled with a graded contrast paper.

Let's say that you have a difficult negative, one that has a contrasty background sky (one that neds a lower contrast to bring out detail) and a slightly underexposed foreground that would normally call for a 3# grade. This is a fairly common negative.

One way of dealing with this situation would be to boost the overall contrast with a #3 filter, then burn in the sky. This may work well, but too much burning in may result in a flat look to the print, even though the exposure is correct. With variable contrast papers you can make the first exposure for the foreground with the #3 filter, then, being careful not to bump the enlarger or changing the focus, replace it with a #1 filter. You then make a second exposure to activate the low contrast layer in the variable contrast paper, dodging the foreground with your hand or an opaque sheet of paper as you do. This takes full advantage of both contrast layers in the paper.

How much burning in should you do? As much as necessary to get the tones right. If you're shooting in a very contrasty lighting situation and can't or don't balance exposure accordingly, you may have to burn in as much as two or three times the overall exposure; even then you may have to go more. But if you find that you always have to burn in anytime you shoot on a bright day you probably are creating your own problems-check your exposure and/or film development procedures.

Copyright text and photo: George Schaub 2010

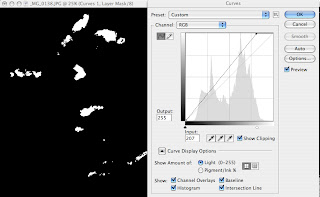

This original was exposed on Tri-X at -2 stops from the significant shadow reading and underdeveloped 10% in D-76 1:1 at 9 minutes to try to hold back density on the highlights. The shadow details were fine but the highlights were quite "hot." The contrast was resolved by burning in the foreground and top of the image. BTW, each lightbulb in the shadow areas was burned in using a small cutout in cardboard.