I have always felt that the photographic print completes the circle begun when I first snapped the shutter. I have also always felt that this was a fairly simplistic and self-evident idea that does not entirely address why I make prints from certain images.

This realization of the exposure via the print justifies, in some sense, the exposure itself; otherwise, why do it? Why bother taking pictures if I do nothing with them? Yet, why does making prints seem like I am doing something with them? Perhaps it’s a holdover from film days, when the only way for people to see an image was to print it, or get it reproduced in a book or magazine, a quasi sort of printing. That’s not the case now when you can go to my or anyone’s web page and see all the images you want.

The print is certainly more permanent, seeing that 95% of all the digital images floating around today will not be able to be read or translated in the future, and many more will be lost on fried hard drives and bent discs and in bankrupt cloud storage companies. Permanence is relative of course, and it’s difficult for me to conceive of 100 years, the average lifespan of pigment inks prints, as permanent.

Obviously there are lots of points and counterpoints to be explored, but to me there is an essential truth about printing that began when, like a lot of folks, I first saw an image emerge from a blank sheet of paper in a tray of chemicals. The print, for me, is an essential part of the photographic process. It is a method of engagement with the work that simply is not satisfied by taking pictures alone. Printing not only requires a skill level that is challenging to achieve, but it brings in numerous mental processes that involve retrospection, introspection, and selective memory.

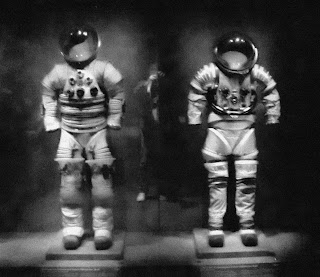

The rendition of the image in a print can also be subject to my mood when making it, to the influence of books and movies and all visual and graphic arts, and perhaps most of all to an accumulated aesthetic approach, one that keeps changing and hopefully evolving. I see the photographic print as having a certain tonal and textural integrity that does not necessarily treat content with any more importance than the treatment of tone itself. In many of my images I notice that the content is there more to serve the tone. Many of the images I seek out to print have a tonal and textural potential rather than any specific contextual meaning or visual message.

This sounds a bit academic but it is sometimes necessary to put these aims into words to understand why one chooses certain images over others to print. Each person has his or her own reasons. Mine come from training and experiences I have undergone that make me believe that a print need establish a certain tonal resonance that satisfies my sense of seeing; these techniques and renditions might be recognizable to others engaged in the craft.

This is not to say that I have not strayed from this aesthetic occasionally, especially when dealing with “low sat” or “low clarity” images. I find these emulations of earlier stages of photography enjoyable and believe that digital processing encourages such behavior. While digital has certainly changed how one goes from image to print it does not really alter why one makes prints or what the potential of the image in a print might be. In fact, it enhances those aspects of printmaking.

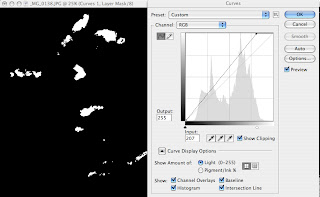

Digital processing and printing shows why people call the digital file a negative—in the strictest photographic sense, like a film negative, it is a sketch or a foundation in which tones and details can be revealed or obscured and the full emotional vision and skills of the photographer can be brought to bear in its final realization, in a print.

The digital file, whether scanned from film or created by a digital camera, creates the first step towards the print. It might provide inspiration or a route to the final image, but without undergoing the printmaking process I don’t believe that a photographer can know why the picture was made, or what sits below the surface of the instinct to push the shutter button. Printmaking requires thought about the image and about myself.

What is perhaps most interesting about the print is what happens between the time the exposure is made and when the print is made—that interval might be a few moments or a few years or, with some images, forty years or more. The actual length of time is not that important—what happens to the instincts, aesthetics and rendition decisions made by the photographer over that period of time is, and it becomes a sort of diary of change, of process, of a visual life. It becomes a mirror into which a photographer can gaze, to make sense of or to just wonder about.

For me any narrative beyond this is speculation to which viewers should not be burdened. I tend to avoid self-description when choosing images to print, as that choice at any moment in time is necessarily instinctive and reactive to that moment’s mood. It is during the printmaking process that I have time to reflect, and when the print is made it becomes a record of all that went into it.

This is my only advice for photographers and printmakers: care for your images so that you will be able to have those moments of retrospection; always value what you have done in the past; use your images as a mirror of the present; and dive deeply into those periods of inspiration that may strike you.

Many of my prints have been cataloged at www.georgeschaubprints.com. Notes on size, print number and occasional mentions of paper surface or other considerations are at that site.

Other images and contact information can be found at www.georgeschaub.com